Written by Alexander Zorin

On 28 December 2025, Professor Vladimir Uspensky passed away in Saint Petersburg, having turned seventy-one in the hospital. I was aware that he had been facing serious health problems related to cancer; nevertheless, his death came as a great shock. He always wrote about his condition with remarkable calm, and I believed it to be under control. We exchanged messages just a few days before his heart stopped, and I could not imagine that this would be the last time I would hear from him.

As recently as April of 2025, Anna Turanskaya, Alla Sizova, and I published an article in the Revue d’Études Tibétaines celebrating the jubilees of Vladimir Leonidovich—as we called him in Russian, following the traditional use of patronymics—and his friend, Professor Anna Tsendina. That article contains all the major information on Uspensky’s academic career and bibliography; there is therefore little sense in repeating it here. Instead, I will highlight only some of the main episodes and achievements, adding a few personal notes.

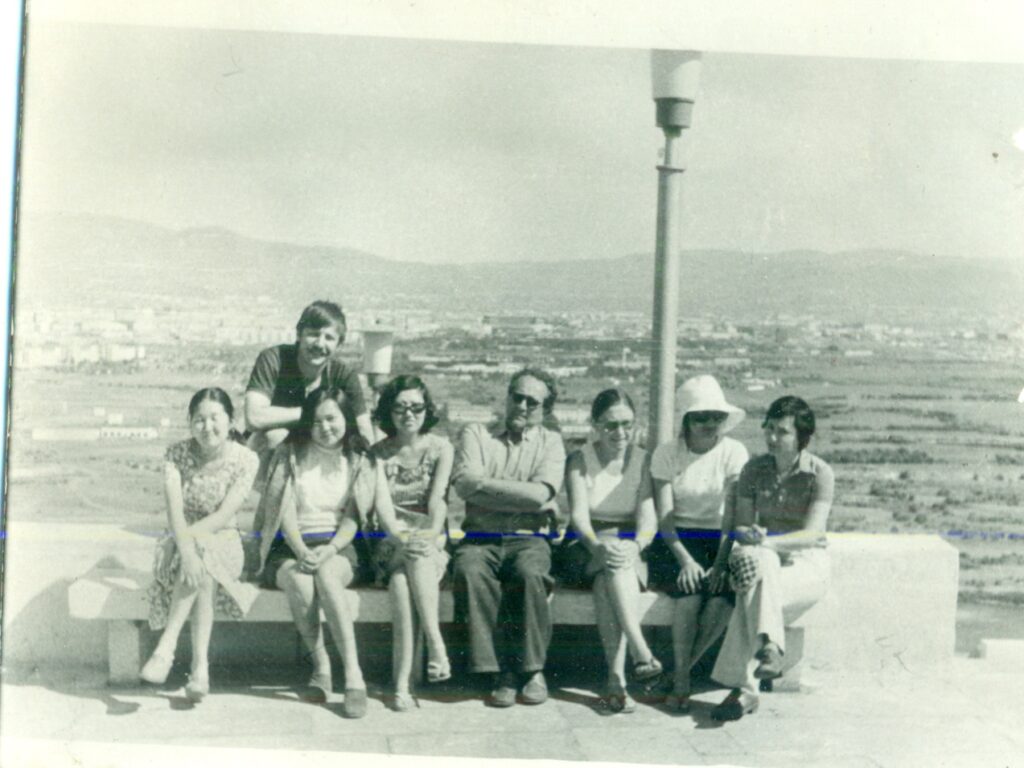

Uspensky studied Mongolian and Tibetan at Leningrad State University from 1975 to 1981. At that time, Bronislav Kuznetsov (1931–1985) was the only professor of Tibetan in the USSR. The photograph below shows Kuznetsov surrounded by his many students and younger colleagues, including Uspensky (fourth from the right, with a moustache and a tie). I received this photograph from Vladimir Uspensky in April 2020, while I was working on a book about the history of Tibetan studies in Russia. Uspensky supported my work greatly, providing several important details related to both well-known and virtually unknown figures.

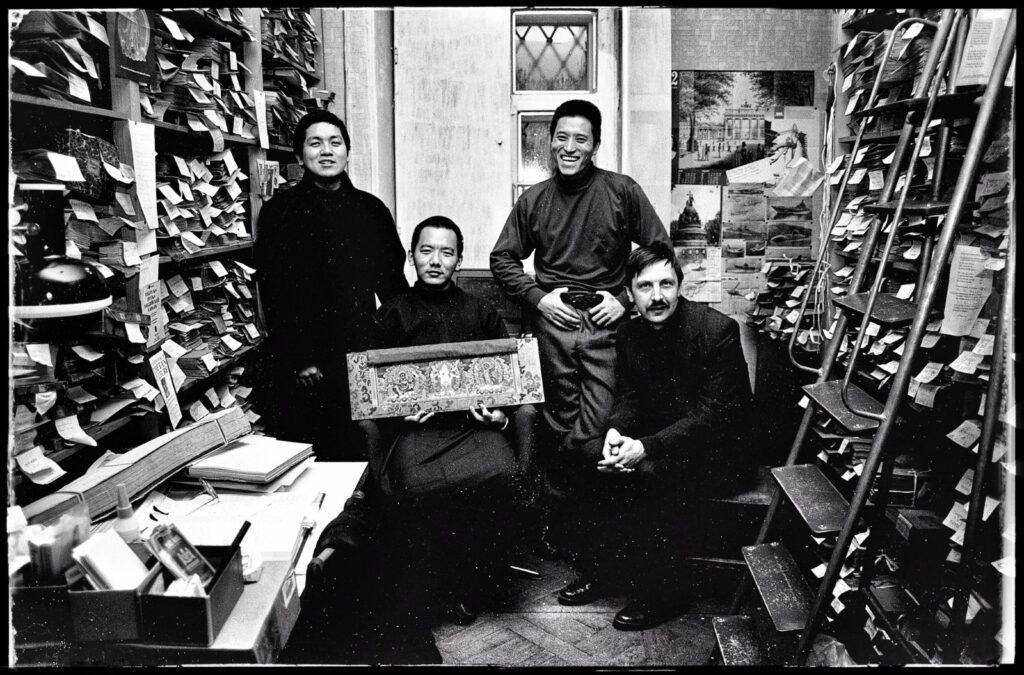

In the same year that this photograph was taken, Uspensky graduated from the university and entered the doctoral program at the Leningrad Branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the USSR Academy of Sciences (now the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, Russian Academy of Sciences – IOM RAS). A passionate lover of old Tibetan and Mongolian books, he always wished to work with the admirable collection of Tibetan manuscripts and block prints preserved at this institute. He was a member of a joint project with the Asian Classics Input Project (ACIP) aimed at cataloguing this collection. From 1992 to 1996, and again from 2002 to 2005, he coordinated, along with Dr. Lev Savitsky (1932–2007), the work of a group of Tibetans from Sera Mey Monastery (Karnataka, India) at the Institute.

Between these two periods, he was a visiting professor in Japan at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies (1996–1997), an experience he always recalled with great warmth, and then he worked intensively on cataloguing the significant collection of Mongolian manuscripts and block prints at Saint Petersburg State University. He was the first to identify and describe the collection of books brought by Vasily Vasilyev (1818–1900) from Beijing to Kazan and then to St Petersburg. Some of these books, as Uspensky ascertained, belonged to the Manchu Prince Yunli (1697–1738), to whom Uspensky dedicated a special monograph (1997).

The discovery of the Vasilyev collection was especially meaningful for Uspensky. As he himself wrote in one of his emails to me (from 29 January 2024; the English translation is mine): “Academician Vasilyev became my idol in my second year at university, when I came across his book, Buddhism. Of course, I understood very little, but I grasped the main point: a scholar of the East must work from sources in Eastern languages”. Uspensky made significant contributions to the history of 19th– and early 20th-century Russian Tibetology and Mongolian studies, which were closely connected to Kazan: many outstanding scholars were born there or nearby, or worked in the city. Tatarstan was also important to him because his wife, the Indologist Elena Uspenskaya (1957–2015), belonged to a subethnic group of Kryashens, sometimes referred to as Baptized Tatars. After her sudden death, she was buried in her native town, Yelabuga (Tatar: Alabuğa), and Uspensky often traveled there to visit her grave. In October 2025, he did so for the last time.

In the same email quoted above, he wrote about another trip: “I visited several places associated with Russian Orientalists: Archimandrite Palladius (Kafarov) and Academician Vasiliev. <…> I look rather worn out, but please judge me leniently—two sleepless nights. The point is not about me, but that this is Kainki, the estate that Vasiliev received as his wife’s dowry. Within the enclosure of this church, he was buried next to his wife. I could not discern any traces of their graves. My sorrowful gaze is directed toward the place where our great predecessor is buried”.

I do not know whether Uspensky adhered to any particular religion. He always spoke about all religious traditions with respect, and he certainly felt particularly close to Orthodox Christianity and Tibetan Buddhism, yet he described himself as a positivist whose worldview was grounded in science. Still, he believed in certain subtle connections that tie people together. When he learned that the date of my birth coincided with the date of his expulsion from the IOM’s Tibetan collection in 2005, he seemed to be convinced it was more than mere coincidence. This is not the place or time to recount in detail his brief tenure as a full-fledged curator of the collection. It suffices to say that the abrupt end of that period was among the saddest days of his life. Later, when I myself became the former curator of this collection, he told me that he had always declined my invitations to visit it, because it is too painful for people to return to a place they loved.

After he began working at Saint Petersburg University in 2007, he developed a new interest in supporting promising students. To his deep regret, however, they eventually all chose to leave the field of Tibetology for more practical pursuits. Nevertheless, he endeavored to introduce new students to Tibetan Buddhist culture, taking them to the historic Saint Petersburg Buddhist Temple Gunzechoinei, with whose abbot, Buda Badmayev (Jampa Donyed Lama), he maintained a friendly relationship.

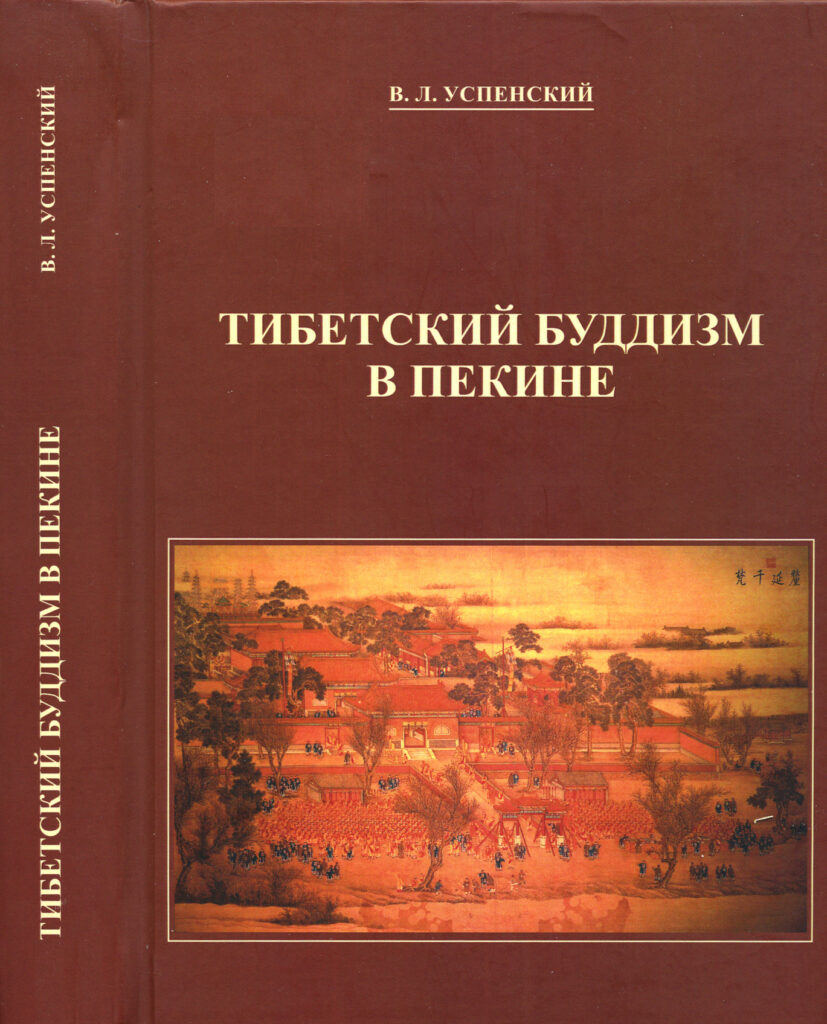

It is very unfortunate that his major Russian-language monograph, Tibetan Buddhism in Beijing (2011), remains untranslated into English. In this book, Uspensky summarized many years of research on the flourishing of Tibetan Buddhism in China’s capital during the Manchu Qing dynasty. He explored a wide range of topics, including the lamas of Beijing and their high-ranking patrons, Buddhist temples, the printing of religious texts, and the creation of religious art objects. I know that he had planned to prepare a second revised edition in Russian. Sadly, that will never happen.

I have many fond and grateful memories of our relationship, beginning in August 2008 when we traveled together, in a large group of scholars, to Lhasa—for both of us, it was the first opportunity to visit Tibet. I am especially grateful to him for the moral support he extended to me when I found myself in emigration in 2022. He even wrote a review of my Habilitation dissertation in 2025—not every colleague in Russia would have had the courage to do so in the current historical context.

Difficult times, like ours, reveal people’s true character. Vladimir Uspensky was a free and decent person, apart from being a great scholar. I will miss him deeply.