Written by Janet Gyatso

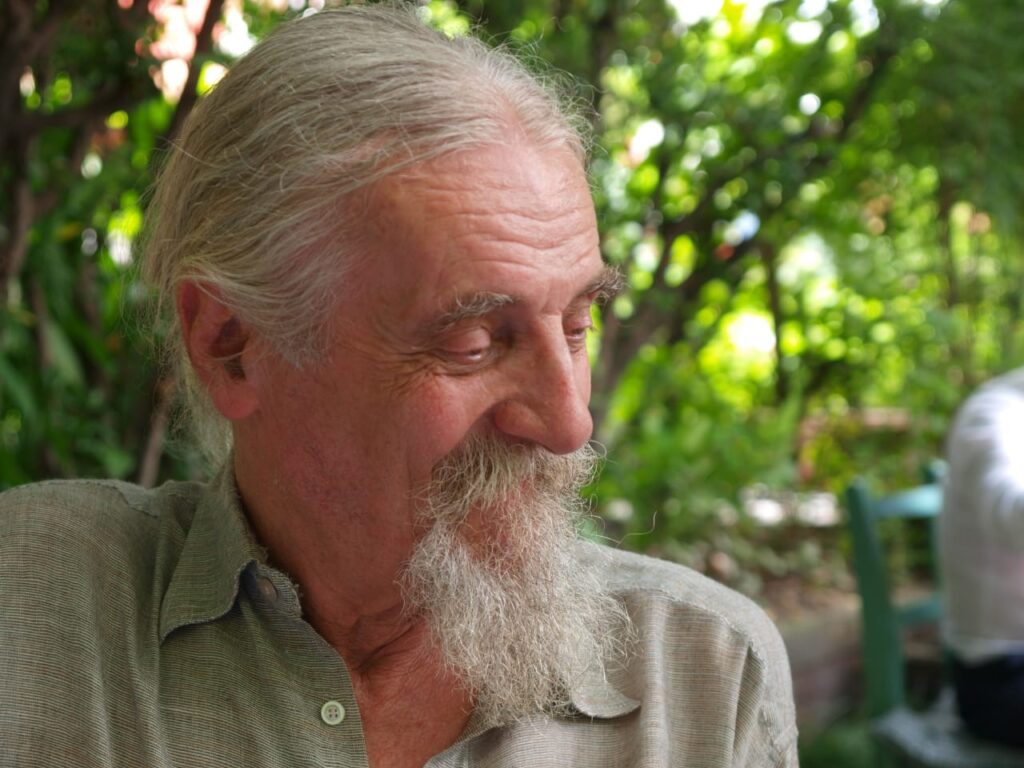

It is with deep sadness that I report the death of Yangga (Dbyangs dga’), ground-breaking historian of Tibetan medicine. He was my teacher, and my student.

Yangga passed away from liver cancer on the evening of December 17, 2022, in Chengdu, China. At the time of his untimely death, at the age of 58, Yangga was Professor (Dge rgan Chen mo) at Bod ljongs Gso rig slob grwa chen mo (University of Tibetan Medicine) in Lhasa [see: http://www.ttmc.edu.cn/info/1018/10288.htm]. Yangga first contracted a liver tumor in around 2015 but he was able to keep working and writing until the last few months of his life. He died at his temporary home in Chengdu, China, where he was living with his wife in order to be near a hospital where he was being treated. His permanent home was in Lhasa and Nagchu. He was joined by his family in the last days after he left the hospital to be able to die at home. He is survived by his wife and two daughters.

Yangga was born in Driru (‘Bri ru) County, Nagchu City, in 1964, where he was educated through high school. He earned a bachelor’s degree from Tibet University in Lhasa in 1989, and another bachelor’s degree from University of Tibetan Medicine in Lhasa in 1991. He earned a master’s degree from University of Tibetan Medicine in 2002. His main teachers in medicine were the famous Khenpo Troru Tsenam (Mkhan po Khro ru rtse rnam) and Khenpo Tsultrim Gyaltsen (Mkhan po Tshul khrims rgyal mtshan). In 2003 he was accepted into the doctoral program in Inner and Altaic Studies at Harvard University, where he worked with myself and Leonard van der Kuijp, and earned his PhD in 2010.

Beginning in 1991 Yangga served as an instructor and then a lecturer at University of Tibetan Medicine. He was promoted to Associate Director of the Dean’s office in 2000. After returning to Lhasa upon graduating from Harvard, he was promoted to Associate Professor in 2013 and full Professor in 2018. Yangga also taught Tibetan language and medicine at Harvard University, and he served as Lecturer in Tibetan in the Department of Asian Languages and Cultures at the University of Michigan during the 2009-2010 academic year. In 2013, he was offered a postdoctoral fellowship to return to the University of Michigan but was unable to accept because he did not receive permission to travel to the United States. In recent years Yangga was Visiting Professor at Southwest University for Nationalities in Chengdu. He was also Deputy Director of the Tibet Autonomous Region Ancient Books Protection Expert Committee, and a member of the Tibetan Medicine Standardization Technical Committee of the Tibet Autonomous Region.

Yangga was only able to present a paper at the International Association of Tibetan Studies (IATS) on one occasion, in Paris 2019 at the 15th IATS Seminar. But he was also on the program for the 14th IATS Seminar in Bergen in 2016 as well. His paper had been accepted and scheduled, but he could not attend at the last minute because his passport for travel was revoked.

I myself have had the great fortune to get to know Yangga well. I first met him in Lhasa at the International Conference on Tibetan Medicine in 2000. At that time I was still teaching at Amherst College, and he was finishing his masters’ degree at the Tibetan Medical University. During the week of that amazing conference in Lhasa, with scores of very learned medical scholars from all over Tibet, we spoke about medicine often. I was quite impressed by the nuance and precision in this young man’s manner of discussing scholarship on Tibetan medicine. And so the following year when I moved to Harvard Divinity School, and I suddenly found myself with the privilege and resources to be able to invite international scholars as visitors, I did so. Yangga was thus able to come to Harvard as a visiting scholar in 2002. Then he went back to Lhasa, and applied into the doctoral program at Harvard in Inner Asian and Altaic Studies, and he was admitted as my advisee. He gained his master’s degree from University of Tibetan Medicine in the same year.

Yangga returned to Harvard in fall 2003 to start his doctoral work. Capable a person as Yangga was, he also managed to get his wife and two young daughters to join him in Somerville, where he lived as a student, within a year’s time. In fact, both children had medical conditions, which Yangga was able to have fixed here in Boston, at our excellent hospitals.

Yangga proceeded to study at Harvard for seven years. He wrote an important doctoral thesis under my direction on the sources of the Tibetan medical classic Rgyud bzhi. In that thesis he provides a detailed comparison of the Rgyud bzhi’s overall chapter structure, as well as the contents of each of those chapters, with the Indic medical classics of Ayurvedic tradition. He shows how in some portions of the work, the Rgyud bzhi is closely dependent on Ayurvedic knowledge. However, in other chapters, its author Yuthok Yontan Gonpo (Gyu thog Yon tan mgon po) was drawing on other medical traditions from both western Asia and East Asia, as well as a range of indigenous medical knowledges on the Tibetan plateau. Yangga identified many of these other medical streams in his thesis with textual precision. He showed how large sections of the Rgyud bzhi are indebted to certain old Tibetan medical works — still extant in Lhasa and to which he and his colleagues there have had access — that predate the Rgyud bzhi and are themselves indebted to various medical traditions not related to Ayurveda. These include Biji poti kha ser, Byang khog dmar byang and Sman dpyad zla ba’i rgyal po.

Next Yangga turned to pay particular attention to the medical knowledge in the Rgyud bzhi on wounds to the upper body. Yangga estimated that this section of Tibetan medicine was connected to empirical knowledge in ancient Tibet regarding how arrows enter the torso in military conflict, and the various surgical procedures to remove them without causing collateral damage in the body.

Yet another important aspect of Yangga’s thesis concerns the families in Tibetan history that were most active in transmitting the Rgyud bzhi in its early years, including the Brang ti lineage of physicians, as well as the Gong sman and Tsha rong families.

Finally, Yangga’s very important contribution was his investigation into the figure of Yuthok Yontan Gonpo the Elder. Yangga speculated that his lifestory and even very existence might have largely been created in the 16th-17th centuries, based on earlier biographical writings which are really about the person whom we now call Yuthok the Younger. In this Yangga was following previous research by outstanding critical Tibetan historians of medicine from the past, with evidence starting in the 13th century at least. Yangga confirms that there is no reference to an “Elder” (as opposed to a “Younger”) Yuthok in pre-16th century Tibetan medical historiography. He also rejects the possibility that there was a physician named Yuthok who served in the royal court of the Tibetan Yarlung dynasty. But most of all, he sets out convincing reasons to attribute the authorship of the Rgyud bzhi to the 12th century figure whom modern scholars have been calling Yuthok the Younger. The Rgyud bzhi was not translated from Sanskrit and is rather a creative and original treatise by the 12th century Tibetan doctor Yuthok Yontan Gonpo, drawing on many medical traditions in Asia and beyond. For the intricate details on this intriguing issue, the reader can consult Yangga’s English articles listed below, one from 2014 and the other from 2019. Even more so, the reader is commended to Yangga’s new book on the life of Yuthok Yonden Gonpo, also listed just below, which he published in the last year of his life, a copy of which I have recently received. I have not yet had the chance to read this book closely, but can say that Yangga provides here six biographical sources for the figure of Yuthok in full, and presents his most up-to-date analysis of the whole issue.

After finishing his thesis and graduating from Harvard, Yangga returned to Tibet and continued to pursue his scholarly work at the same time that he took up teaching and administrative duties. He continued his deep research in the various archives and libraries of Lhasa, and wrote many articles. A full c.v. of his works is being prepared and may be requested from me when it is ready. Most notably, he published three substantial books, including editions of valuable and rare original documents, during the last year of his life. Each of these volumes make major contributions to the study of Tibetan medicine.

Bod lugs gso ba rig pa’i khog dbub gces btus rin chen phreng ba, Lhasa: Bod ljong bod yig dpe rnying dpe skrun khang. 2022. 440 pp. (Selected rare historical writings on Tibetan medicine).

Gyu thog gsar rnying gi rnam thar dang de’i skor gyi dpad pa drang gtam rna ba’i bu ram. Chengdu: Si khron mi rigs dpe skrun khang, 2022. 360 pp. (Research on the Elder and Younger Yuthok Yontan Gonpos, including six Yuthok biographies).

Bi ji’i po ti kha ser dang de’i dpyad pa pa dgyes pa’i gtam, Lhasa: Bod ljong bod yig dpe rnying dpe skrun khang. 2022. 321 pp. (Two versions of, and research on, an early medical work in Tibetan which presents medical knowledge from Western Asia and beyond.)

Additionally, Yangga edited and compiled material for other volumes, including a catalogue of the medical texts held at Sku ‘bum Moastery, published by Kan suʼu mi rigs dpe skrun khang in 2001, and a volume on the scientific research methods and procedures of Tibetan medicine published by Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang, in Lhasa in 2017.

Some of Yangga’s work on the multiple medical traditions converging in Rgyud bzhi was addressed in the paper he delivered at the 15th IATS seminar in Paris in 2019, entitled “Preliminary Investigations into Shang Siji Bar [Zhang gzi brjid ‘bar’] and His Medical Works.” He has published numerous other scholarly articles in Tibetan in China, including a study of rDzong ‘phreng ‘phrul gyi lde mig. Additionally, he is co-author of numerous articles with other scholars of Tibetan medicine, including an analysis of the anti-rheumatic effects of huang lian jie du tang from a network perspective; an investigation and analysis of employment psychology of students in Tibetan professional colleges; an analysis of cynandione A’s anti-ischemic stroke effects; and a piece on Tibetan veterinary documents from Dunhuang in France.

Among his publications in English are “The Origin of the Four Tantras and an Account of Its Author, Yuthog Yonten Gonpo ” in Bodies in Balance: The Art of Tibetan Medicine, ed. Theresia Hofer,New York: Rubin Museum of Art in conjunction with Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2014, 154-177; and “A Preliminary Study on the Biography of Yutok Yönten Gönpo the Elder: Reflections on the Origins of Tibetan Medicine,” in Knowledge and Context in Tibetan Medicine, ed. William A. McGrath, Leiden/Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, 2019, 59-84. Both of these essays will give the reader a good idea of the intricate arguments and evidence Yangga amassed and analysed to establish the historical authorship of the medical classic Rgyud bzhi in the 12th century. Another important article in English is his “A Comparative Study of the Relationship between Greek and Tibetan Medicine” in Journal of Tibetan and Himalayan Studies, 2018, 73-87.

Another area of Yangga’s many interests was the origins of the medicinal baths tradition in Tibetan medicine. The paper he had planned to deliver at the IATS conference in Bergen was entitled “Study on the Origin of Tibetan Five Nectars Medicated Bath Therapy.” He has published about the matter in several articles in China in 2016.

While I do not know much about the service that Professor Yangga performed for his school and with colleagues inside Tibet at other universities and medical centers, I do know about one big effort in which he was involved. This came after the bid on the part of the Indian government to claim gso ba rig pa as an Indian “intangible cultural heritage” as specified by UNESCO and therefore under Indian jurisdiction and copyright. Who better to refute that too-simplistic claim about. the origin of gso rig than Yangga himself? He consulted with me while he was laboriously preparing the appropriate arguments for the Tibetan origin of the Rgyud bzhi, together with his colleague at University of Tibetan Medicine, Mingji Cuomu. Then Yangga and Yum pa, astrologer and Vice–President of the Lhasa Men-Tsee-Khang (Sman rtsis khang), finally travelled to Bogota, Columbia in 2019 from 9th to 14th December to testify in front of the 14th session of the Intergovernmental Committee on Intangible Cultural Heritage within UNESCO, and the case was decided in the favor of China.

I mourn the thought that Yangga will not be able to produce more ground-breaking work on the history and theory of Tibetan medicine, and be able to mentor many more students. But more sorrowfully yet, I mourn the loss of Yangga the person, the man, the father, the friend. In addition to working with him throughout his time at Harvard, I later had the fortune to tour Lake Kokonor 2016 with him on a visit to Xining. I also visited his family at their home in Lhasa when I attended another medical conference in Lhasa, this time hosted on 12–13 September 2016 by the Lhasa Men–Tsee–Khang, along with the Tibetan Medicine Committee of the World Federation of Chinese Medicine Societies, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of the establishment of the Sman rtsis khang in Lhasa by the 13th Dalai Lama.

I consider Yangga to have been my teacher because of his expert guidance and instruction when I was reading the history of medical thought in Tibet for my own research, over a period of seven years while he was at Harvard. It is no exaggeration to say that I could never have been able to write the book that I did, Being Human in a Buddhist World: An Intellectual History of Tibetan Medicine (2015), without the extensive discussions we had during that time.

Yangga had an extremely warm personality. One of my favorite memories is from one evening when he and his family were at my husband’s and my home for dinner. I remember Yangga’s two little daughters hiding behind the door to the dining room as he sat at our table, peeking out and giggling at him. They kept interrupting the adult conversation we were carrying on at the table. But Yangga was not at all annoyed; in fact he could barely hold back his own giggles at their pranks.

I also remember a conversation we once had about a negative colleague. Yangga opined, “Everyone has a beautiful smile. XX is one of the rare few who doesn’t, hahahaha!” I actually regard that as a profound and compassionate observation — as well as a case of the exception proving the rule. Everyone’s face has its own beauty.

Yangga took a huge amount of joy in life. He expressed it with a deep and resounding laugh, and he laughed a lot — at himself, at others, at whatever was true. I can hear that laugh in my head right now; too bad I cannot convey it on the page. A favorite memory from recent times is of sitting with him and many of the other Tibetan delegates to the Paris IATS meeting in July 2019, on the roof of a sight-seeing bus. As we floated around Paris and admired the wonderful sights and architecture, we simultaneously were engaged in a bus-wide contest of trading insults, barbs, and smart-aleck comments, mostly about each other. Yangga was one of the ringleaders and sharpest in the group. He came out with some hilarious observations (only a few of which I could truly follow, but the infectious laughter all over the bus had me laughing anyway).

Yangga had a very keen sense of people’s character. He plumbed the depth of their sincerity, and was attuned to how they try to come across. After all, not only was Yangga a historian of medicine, he was a full-fledged physician who had learned well the art of diagnosis, although he did not practice often. A big part of what a doctor needs to do is to read your outer signs for what they portend about what is going on inside of you. Indeed, the entire field of logic in Indian philosophy, including the arts of induction and deduction, had its first major articulation in the classical Indian medical works.

I found Yangga to be a most intelligent conversation partner, and enjoyed many deep discussions with him about Tibetan history and culture. He was not completely traditional in the sense of being unwilling to question received wisdom, although his education with Khenpo Troru Tsenam and Khenpo Tsultrim Gyaltsen was indeed very much in line with old Tibetan medical pedagogy rather than modern critical academic method. Yangga was very critical of rhetoric, and had a talent for spotting unspoken agendas. He was also deeply aware of the importance and status of evidence — and the implications of the lack thereof — in historiography. in many ways Yangga was a perfect example of the keen values and capabilities that the very texts I was reading with him were promoting as the virtues of the ideal doctor. Yangga taught me to recognize sarcasm and irony, for example, in the way that Zur mkhar ba Blo gros rgyal po portrayed the authorship of Rgyud bzhi, which I never would have recognized on my own. And I remember him chuckling on many occasions at the audacity of some of Sde srid Sangs rgyas rgya mtsho’s own barbs about his colleagues and his fierce criticism thereof.

Yangga too was fierce as a professional academic. He told me that when he returned to Lhasa and gave a talk to an audience of Tibetan doctors and scholars on the paucity of evidence that our stories about Yuthok the Elder are historically true, some of the elder scholars in the audience wept. Poignant as the moment was, the story also shows that in order to weep, his audience must have been convinced by him. And that shows their own basic respect for facts, evidence, and historiographical reasoning — all mainstay values in traditional Tibetan medical pedagogy and scholasticism.

I perceived the gravity of Yangga’s physical condition by early 2022, when he had to return to the hospital for more treatment. I was gripped by a sudden fear he might die. I shared my fear with him in a text message — we were corresponding on about a monthly basis. He wrote back to me, “My mind is fine. I am not so worried about the disease. It depends on my own karma.”

He also told me at that time the names of some of his students, including his best ones, of which there are now many. And we discussed the location of some important manuscripts, although Yangga reminded me that the majority of the rare ancient medical manuscripts that were preserved in the Potala have recently all been published and distributed to libraries around the world. The main set, edited by Ye shes Yang ‘dzoms and Yum pa, is entitled Gangs ljongs sman rtsis rig mdzod chen mo, Bejing, Bod rig pa dpe skrun khang, 2016 and consists in 130 vols. A second set of 30 volumes, also from the Potala, is entitled Krung go’i bod lugs gso rig rtsa che’i dpe rnying kun btus or China’s Traditional Tibetan Medical Texts, and was compiled by Gso rig slob grva chen mo under the direction of Nyi ma Tshe ring and published in Lhasa in 2013 by Bod ljongs mi dmangs dpe skrun khang.

According to his own wishes and instructions, Yangga’s body was brought back from Chengdu, carried by his younger brother. It was cremated in the great holy site of Samye Chimphu, according to Gen Yanggala’s own wishes.

Deep thanks to Tsultrim Padmo Drushik, Karma Topdhen, William McGrath, Yangbum Gyal, Sun Penghao, Yumpa, Mingji Cuomo, Donald Lopez, Hanna Havnevik, and Leonard van der Kuijp for providing information contributing to this Obituary.