Collecting the memories of the pioneers of Tibetan Studies

In Memoriam: Tsuguhito Takeuchi (1951–2021)

Tsuguhito Takeuchi, a linguist, philologist, and an eminent and leading scholar in the field of Old Tibetan Studies, passed away on Saturday, 3 April 2021, at home after a two-year-long struggle against an illness. For many years, he was one of the central figures of the IATS seminars and, from 2013 onward, served as the Japanese representative on its advisory board.

He was born in Amagasaki, Hyogo, in 1951 as the second son—the elder son had prematurely passed away—of the 19th head priest at a Buddhist temple, Josen-Ji. His father was Professor Shoko Takeuchi, a renowned scholar of Buddhist studies. Takeuchi was raised in an academic atmosphere wherein his father’s colleagues and students often gathered and discussed Buddhist studies in his home. However, having entered Kyoto University, he chose linguistics, which was a relatively new academic field at the time.

In 1978, after initial training in linguistics by Professor Tatsuo Nishida, a renowned linguist of Sino-Tibetan languages, particularly for the decipherment of Tangut script, Takeuchi completed his master’s thesis on the sentence structure of the modern Tibetan language. He analysed the spoken words of his teacher, Professor Tshul-khrims skal-bzang, by using the most advanced contemporary theory of case grammar. His thesis was first published in 1990 as an article in Asian Languages and General Linguistics, the Festschrift for Professor Nishida, and then translated into English in 2016: ‘The Function of Auxiliary Verbs in Tibetan Predicates and their Historical Development’. He was an outstanding and pioneering student in the field of linguistics, which was not yet popular at Kyoto University.

In August 1978, he conducted his first linguistic field research on the Dingri dialect in Jawalakhel, Nepal. Dingri is close to Zur tsho, where his teacher Professor Tshul khrims skal bzang was born. However, Professor Tshul khrims skal bzang was educated at the Sera Monastery in Lhasa from when he was 10 years old and thus spoke the so-called ‘Central Tibetan dialect’.

In July 1979, after spending a month at the University of Texas as a graduate student of the Fulbright Orientation Program, he studied linguistics at the University of Pennsylvania for a year. He then decided to move to Indiana University, where Professor Helmut Hoffmann was teaching, to learn the Tibetan language. Unfortunately, Professor Hoffmann retired six months later for reasons of ill-health. Nevertheless, Takeuchi continued to study under Professor Cristopher Beckwith, who sparked his lifelong research interest in Old Tibetan Studies.

Takeuchi took Professor Beckwith’s Old Tibetan class and embarked on a philological study of Old Tibetan documents. They read parts of the Old Tibetan Annals, parts of the Chronicle, the Samye Inscription, and the Prophecy on the Decline of Buddhism in Khotan, among other texts. Professor Beckwith remembers that Takeuchi was a brilliant student, very cheerful and kind, and always very helpful towards his teacher.

In 1982, as a doctoral student at Indiana University, Takeuchi made an outstanding debut in the 3rd IATS seminar held at Columbia University with a paper entitled ‘A Passage from the Shih chi in the Old Tibetan Chronicle’. He had found a passage in the Old Tibetan Chronicle that was an adaptation from the Chinese historical record Shiji, with which he was familiar from his childhood days.

In this way, during his days at Indiana University, he met excellent teachers and lifelong friends: Professor Beckwith; Professor Thubten Jigme Norbu, who was the Dalai Lama’s older brother; Professor Dan Martin; and Professor Elliot Sperling, among others.

Takeuchi’s research method was simple and straightforward: collect all related documents and analyse the text as a whole. He disliked ad hoc reading and interpretation, and always tried to collect parallel and similar expressions as far as possible. This is probably the most basic way to read a text in the absence of good dictionaries. Nevertheless, in reality, it was a tremendously challenging job simply because many Old Tibetan manuscripts remained unpublished at the time. He was also never satisfied with the edited text and sometimes said, ‘I only believe the original manuscript that I see with my naked eyes’. He regarded manuscripts not only as textual media but also in material terms, such as in terms of the shape of paper and the size, and thickness of wood. He spared no pains to go everywhere to see the original manuscripts, including London, Paris, Helsinki, Berlin, St. Petersburg, and Xinjiang. His hands-on approach led him to many unpublished and uncatalogued manuscripts.

He then collected 55 contracts from many Old Tibetan manuscripts worldwide and finished his Ph.D. dissertation. It was published in 1995 as a monograph titled Old Tibetan Contracts from Central Asia, one of the essential works in Old Tibetan Studies until the present day.

He continued to catalogue the Old Tibetan manuscripts: Choix de documents tibétains conservés à la Bibliothèque Nationale, Tome III in 1990 and Tome IV in 2001, Old Tibetan Manuscripts from East Turkestan in the Stein Collection of the British Library, 3 vols. in 1997–98, Old Tibetan Inscriptions in 2009, Old Tibetan Texts in the Stein Collection Or. 8210 in 2012, and Tibetan Texts from Khara-khoto in the Stein Collection of the British Library in 2016. This was detail-oriented work, or ‘slave-work’ as he liked to put it. However, he achieved it through persistent efforts. Using his sincere efforts, his smile and his friendliness as leverage, he built the trust of librarians and scholars, who allowed him to enter the stacks where many unpublished manuscripts were kept. He checked these manuscripts one by one, read them, sometimes corrected the numbering, and even found lost manuscripts.

Regarding his academic career, immediately after returning from the United States to Japan he was first appointed as a full-time lecturer at Kinki University in 1984. He then moved to the Kyoto University of Education in 1988 and to the Kobe City University of Foreign Studies in 1997, where he stayed until his retirement in 2017 at the age of 65. He was also appointed as the director of the International Office in 2009 and the director of the Research Institute in 2011 and served as the dean of the graduate school during 2011–2013.

He was also eager to cultivate the next generation of Old Tibetan scholars, and launched a private class for reading Old Tibetan texts in 1998. It was held once a week, sometimes once a month, in his office at Kobe City University of Foreign Studies until his retirement in 2017. The first text we read together was Old Tibetan Chronicle, which he had read along with Professor Beckwith at Indiana University. Then, we read many and various texts with him: official documents of the Old Tibetan Empire such as Pelliot tibétain 1089, private letters, Khotanese prophecies, divination texts, etc. He shared many things with us, including the reading skill required for Old Tibetan texts and the gossip of Tibetologists.

His private class was not only the reading group but also an academic salon. We freely discussed numerous topics in a relaxed mood and an informal setting. We discussed numerous new projects, some of which became a reality, such as the Old Tibetan Documents Online project; the publication of some catalogues; and the organisation of several conferences, including the 57th Conference of the Japanese Association for Tibetan Studies, the 17th Himalayan Languages Symposium, the Third International Seminar of Young Tibetologists, theInternational Seminar on Tibetan Languages and Historical Documents, and several Old Tibetan panels in the IATS seminar. We also proposed new ideas, which were eventually published as individual papers. Through discussions with him, we learned how to develop a logical argument and to write an academic paper.

Unquestionably, Takeuchi opened a new path in Old Tibetan Studies and was a crucial person in Tibetan scholarship in Japan. With his outstanding contributions and a brilliant legacy, he remained cheerful, kind and helpful to young scholars just as he had been in his university days. Everybody who met Takeuchi knows that he loved joking, drinking with friends, and watching football. He always said that he could bring good weather with him wherever he was, and he proved it repeatedly. We respect him as a great scholar and generous teacher and also loved him as a person. We will remember his shining smile whenever we have a drink or look up at the blue sky.

Kazushi Iwao

Ai Nishida

IATS 2022 CfP deadline extended

Dear colleagues,

we would like to thank all of you who have already submitted a proposal for the upcoming IATS Seminar. We received so many interesting and cutting edge research topics! And since some of you have contacted us in regards to the extension of the submission deadline, we are now officially extending the deadline to the 30th of September. So those of you who were not yet able to submit your topics, please do it so in the near future.

Good luck during the review process and see you soon in Prague!

IATS 2022 team

༄༅། །བཀུར་འོས་མཁྱེན་ལྡན་རྣམས་ལ་ཆེད་གསོལ།

འཆར་ལོའི་རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་བོད་རིག་པའི་བགྲོ་གླེང་ཆེད་དེ་སྔོན་དཔྱད་རྩོམ་སྙིང་དོན་གོང་འབུལ་གནང་ཟིན་པ་ཀུན་ལ་འདི་གའི་གོ་སྒྲིག་ཚོགས་པ་ནས་ཐུགས་རྗེ་ཆེ་ཞུ། ད་ལམ་ང་ཚོར་གསར་དཔྱད་ཀྱི་རང་བཞིན་ལྡན་པ་དང་ཡིད་འགུལ་ཐེབས་པའི་བརྗོད་བྱ་མང་པོ་འབྱོར་སོང་། འོན་ཀྱང་མཁྱེན་ལྡན་རེ་འགས་དཔྱད་རྩོམ་སྙིང་དོན་གོང་འབུལ་ཞུ་བའི་དུས་བཀག་བཅད་མཚམས་དེ་ཕྱི་སྣུར་ཡོང་ཐབས་རེ་སྐུལ་གནང་བ་ལ་བརྟེན་ནས་འདི་ནས་ང་ཚོས་ཀྱང་གཞུང་འབྲེལ་གྱིས་༢༠༢༡ལོའི་ཟླ་བ་༩པའི་ཚེས་༣༠བར་དུས་བཀག་བཅད་མཚམས་དེ་དུས་འགྱངས་བཏང་ཡོད་པས། དེ་སྔོན་དཔྱད་རྩོམ་སྙིང་དོན་གོང་འབུལ་ཞུ་མ་ཐུབ་པ་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་གང་མགྱོགས་སུ་གོང་འབུལ་གནང་བར་འབོད་སྐུལ་ཞུ་བཞིན་ཡོད།

ཁྱེད་ཀྱི་དཔྱད་རྩོམ་སྙིང་དོན་འདེམས་ཐོན་ཡོང་བ་དང་པ་རག་ནས་མཇལ་བའི་རེ་སྨོན་ཡོད།

འཚོགས་ཐེངས་བཅུ་དྲུག་པའི་གོ་སྒྲིག་ཚོགས་པ་ནས།

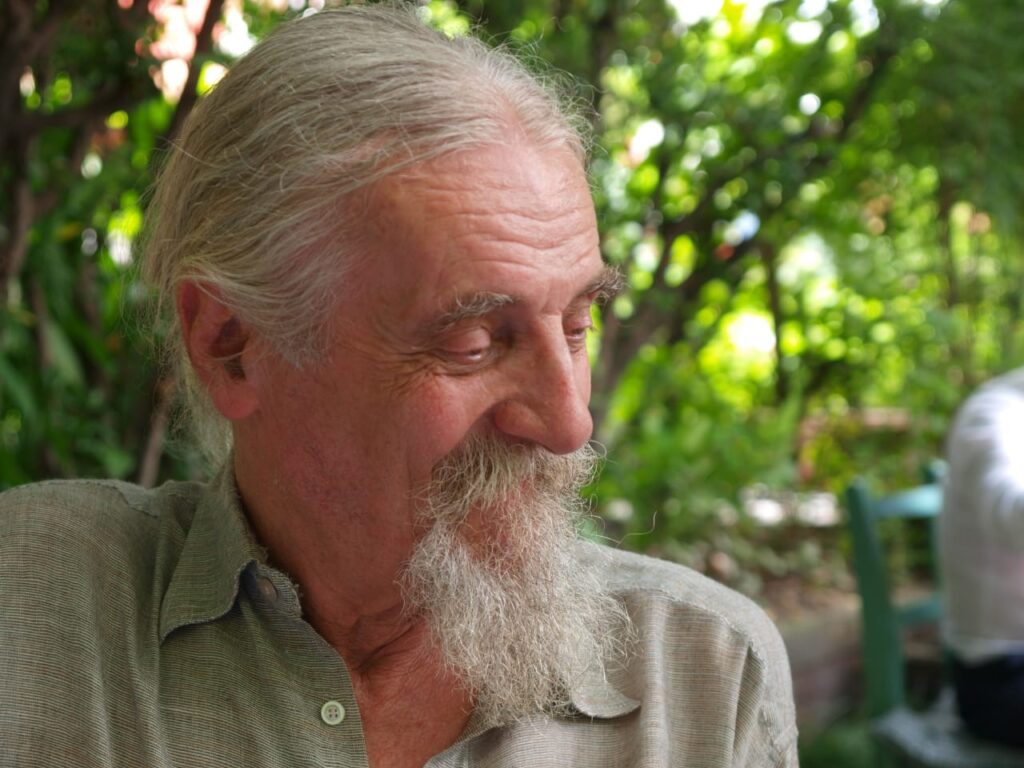

In Memoriam: Hubert Decleer (1940–2021)

With great sadness, we share news that our incomparable teacher, mentor, colleague, and friend Hubert Decleer passed away peacefully on Wednesday, August 25. He was at his home with his wife, the poet Nazneen Zafar, in Kathmandu, Nepal, near the Swayambhū Mahācaitya that had been his constant inspiration for nearly five decades. His health declined rapidly following a diagnosis of advanced-stage lung cancer in May, but he remained lucid and in high spirits and over the past weeks he was surrounded by family members and close friends. Through his final hours, he maintained his love of Himalayan scholarship and black coffee, and his deep and quiet commitment to Buddhist practice.

Hubert’s contributions to the study of Tibetan and Himalayan traditions are expansive, covering the religious, literary, and cultural histories of Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, and India. For nearly thirty-five years he directed and advised the School for International Training’s program for Tibetan Studies, an undergraduate study-abroad program that has served as a starting point for scholars currently working in fields as diverse as Anthropology, Art History, Education, Conservation, History, Religious Studies, Philosophy, and Public Policy. The countless scholars he inspired are connected by the undercurrent of Hubert’s indelible “light touch” and all the subtle and formative lessons he imparted as a mentor and friend.

Hubert’s contributions to the study of Tibetan and Himalayan traditions are expansive, covering the religious, literary, and cultural histories of Tibet, Nepal, Bhutan, and India. For nearly thirty-five years he directed and advised the School for International Training’s program for Tibetan Studies, an undergraduate study-abroad program that has served as a starting point for scholars currently working in fields as diverse as Anthropology, Art History, Education, Conservation, History, Religious Studies, Philosophy, and Public Policy. The countless scholars he inspired are connected by the undercurrent of Hubert’s indelible “light touch” and all the subtle and formative lessons he imparted as a mentor and friend.

Hubert embodied a seemingly inexhaustible curiosity that spanned kaleidoscopic interests ranging from Chinese landscapes to Netherlandish still lifes, medieval Tibetan pilgrimage literature to French cinema, 1940s bebop to classical Hindustani vocal performance. With legendary hospitality, his home, informally dubbed “The Institute,” was an oasis for scholars, former students, artists, and musicians, who came to share a simple dinner of daal bhaat or a coffee on the terrace overlooking Swayambhū. The conversations that took place on that terrace often unearthed a text or image or reference that turned out to be the missing link in the visitor’s current research project. When not discussing scholarship, Hubert inspired his friends to appreciate the intelligence and charm of animals—monkeys and crows especially—or to enjoy the marvels of a blossoming potted plum tree. His attentiveness to the world around him generated intense sensitivity and compassion. He was an accomplished painter and a captivating storyteller, ever ready with accounts of the artists’ scene in Europe or his numerous overland journeys to Asia. The stories from long ago flowed freely and very often revealed some important insight about the present moment, however discrete.

Hubert François Kamiel Decleer was born on August 22, 1940, in Ostend, Belgium. In 1946, he spent three months in Switzerland with a group of sixty children whose parents served in the Résistance. He completed his Latin-Greek Humaniora at the Royal Atheneum in Ostend in 1958, when he was awarded the Jacques Kets National Prize for biology by the Royal Zoo Society of Antwerp. He developed a keen interest in the arts, and during this period he also held his first exhibition of oil paintings and gouaches. In 1959 he finished his B.A. in History and Dutch Literature at the Regent School in Ghent. Between 1960 and 1963 he taught Dutch and History at the Hotel and Technical School in Ostend, punctuated by a period of military service near Köln, Germany in 1961–62. The highlight of his military career was the founding of a musical group (for which he played drums) that entertained officers’ balls with covers of Ray Charles and other hits of the day.

Hubert François Kamiel Decleer was born on August 22, 1940, in Ostend, Belgium. In 1946, he spent three months in Switzerland with a group of sixty children whose parents served in the Résistance. He completed his Latin-Greek Humaniora at the Royal Atheneum in Ostend in 1958, when he was awarded the Jacques Kets National Prize for biology by the Royal Zoo Society of Antwerp. He developed a keen interest in the arts, and during this period he also held his first exhibition of oil paintings and gouaches. In 1959 he finished his B.A. in History and Dutch Literature at the Regent School in Ghent. Between 1960 and 1963 he taught Dutch and History at the Hotel and Technical School in Ostend, punctuated by a period of military service near Köln, Germany in 1961–62. The highlight of his military career was the founding of a musical group (for which he played drums) that entertained officers’ balls with covers of Ray Charles and other hits of the day.

In 1963 Hubert made the first of his many trips to Asia, hitchhiking for thirteen months from Europe to India and through to Ceylon. Returning to Belgium in 1964, he then worked at the artists’ café La Chèvre Folle in Ostend, where he organized fortnightly exhibitions and occasional cultural events. For the following few years he worked fall and winter for a Belgian travel agency in Manchester and Liverpool, England, while spending summers as a tour guide in Italy, Central Europe, and Turkey. In 1967 he began working as a guide, lecturer, and interpreter for Penn Overland Tours, based in Hereford, England. In these roles he accompanied groups of British, American, Australian, and New Zealand tourists on luxury overland trips from London to Bombay, and later London to Calcutta—excursions that took two and a half months to complete. He made twenty-six overland journeys in the course of fourteen years, during which time he also organized and introduced local musical concerts in Turkey, Pakistan, India, and later Nepal. He likewise accompanied two month-long trips through Iran with specialized international groups as well as a number of overland trips through the USSR and Central Europe. In between his travels, Hubert wrote and presented radio scenarios for Belgian Radio and Television (including work on a prize-winning documentary on Nepal) and for the cultural program Woord. The experiences of hospitality and cultural translation that Hubert accumulated on his many journeys supported his work as a teacher and guide; he was always ready with a hint of how one might better navigate the awkward state of being a stranger in a new place.

With the birth of his daughter Cascia in 1972, Hubert’s travels paused for several years as he took a position tutoring at the Royal Atheneum in Ostend. He also worked as an art critic with a coastal weekly and lectured with concert tours of Nepalese classical musicians, cārya dancers, and the musicologist and performer Michel Dumont.

In 1975, during extended layovers between India journeys, Hubert began a two-year period of training in Buddhist Chinese at the University of Louvain with pioneering Indologist and scholar of Buddhist Studies Étienne Lamotte. He recalled being particularly moved by the Buddhist teachings on impermanence he encountered in his initial studies. He also worked as a bronze-caster apprentice and assistant to sculptor—and student of Lamotte—Roland Monteyne. He then resumed his overland journeying full time, leading trips from London to Kathmandu. These included annual three-month layovers in Nepal, where he began studying Tibetan and Sanskrit with local tutors. He was a participant in the first conference of the Seminar of Young Tibetologists held in Zürich in 1977. In 1980 he settled permanently in Kathmandu, where he continued his private studies for seven years. During this period he also taught French at the Alliance Française and briefly served as secretary to the Consul at the French Embassy in Kathmandu.

It was during the mid 1980s that Hubert began teaching American college students as a lecturer and fieldwork consultant for the Nepal Studies program of the School for International Training (then known as the Experiment in International Living) based in Kathmandu. In 1987 he was tasked with organizing SIT’s inaugural Tibetan Studies program, which ran in the fall of that year. Hubert served as the program’s academic director, a position he would hold for more than a decade. Under his direction, the Tibetan Studies program famously became SIT’s most nomadic college semester abroad, regularly traveling through India, Nepal, Bhutan, as well as western, central, and eastern Tibet. It was also during this period that Hubert produced some of his most memorable writings in the form of academic primers, assignments, and examinations. In 1999 Hubert stepped down as academic director to become the program’s senior faculty advisor, a position he held until his death.

Hubert taught and lectured across Europe and the United States in positions that included visiting lecturer at Middlebury College and Numata visiting faculty member at the University of Vienna.

Hubert taught and lectured across Europe and the United States in positions that included visiting lecturer at Middlebury College and Numata visiting faculty member at the University of Vienna.

Hubert’s writing covers broad swaths of geographical and historical territory, although he paid particular attention to the Buddhist traditions of Tibet and Nepal. His research focused on the transmission history of the Vajrabhairava tantras, traditional narrative accounts of the Swayambhū Purāṇa, the sacred geography of the Kathmandu Valley (his 2017 lecture on this topic, “Ambrosia for the Ears of Snowlanders,” is recorded here), and the biographies of the eleventh-century Bengali monk Atiśa. His style of presenting lectures was rooted in his work as a musician and lover of music—he prepared meticulously to be sure his talks were rhythmic, precise, and yet had an element of the spontaneous. One of his preferred mediums was the long-form book review, which incorporated new scholarship and original translations with erudite critiques of subjects ranging from Buddhist philosophy to art history and Tibetan music. His final publication, a forthcoming essay on an episode contained in the correspondence of the seventeenth-century Jesuit António de Andrade (translated by Michael Sweet and Leonard Zwilling in 2017), uses close readings of Tibetan historical sources and paintings to complicate and contextualize Andrade’s account of his mission to Tibet. This exemplifies the spirit and method of his review essays, which demonstrate his deep admiration of published scholarship through a meticulous consideration of the work and its sources, often leading to new discoveries.

In addition to Hubert’s published work, some of his most endearing and enduring writing has appeared informally, in the guise of photocopied packets intended for his students. Each new semester of the SIT Tibetan Studies program would traditionally begin with what is technically called “The Academic Director’s Introduction and Welcome Letter.” These documents would be mailed out to students several weeks prior to the program, and for most other programs they were intended to inform incoming participants of the basic travel itinerary, required readings, and how many pairs of socks to pack. The Tibetan Studies welcome letter began as a humble, one-page handwritten note, impeccably penned in Hubert’s unmistakable hand.

Hubert’s welcome letters evolved over the years, and they eventually morphed into collections of three or four original essays covering all manner of subjects related to Tibetan Studies, initial hints at how to approach cultural field studies, new research, and experiential education, as well as anecdotes from the previous semester illustrating major triumphs and minor disasters. The welcome letters became increasingly elaborate and in later years regularly reached fifty pages or more in length. The welcome letter for fall 1991, for example, included chapters titled “Scholarly Fever” and “The Field and the Armchair, and not ‘Stage-Struck’ in either.” By spring 1997, the welcome letter included original pieces of scholarship and translation, with a chapter on “The Case of the Royal Testaments” that presented innovative readings of the Maṇi bka’ ’bum. Only one element was missing from the welcome letter, a lacuna corrected in that same text of spring 1997, as noted by its title: Tibetan Studies Tales: An Academic Directors’ Welcome Letter—With Many Footnotes.

Hubert was adamant that even college students on a study-abroad program could undertake original and creative research, either for assignments in Dharamsala, in Kathmandu or the hilly regions of Nepal, or during independent-study projects themselves, which became the capstone of the semester. Expectations were high, sometimes seemingly impossibly high, but with just the right amount of background information and encouragement, the results were often triumphs.

Hubert regularly spent the months between semesters, or during the summer, producing another kind of SIT literature: the “assignment text.” These nearly always included extensive original translations of Tibetan materials and often extended background essays as well. They would usually end with a series of questions that would serve as the basis for a team research project. For fall 1994 there was “Cultural Neo-Colonialism in the Himalayas: The Politics of Enforced Religious Conversion”; later there was the assignment on the famous translator Rwa Lotsāwa called “The Melodious Drumsound All-Pervading: The Life and Complete Liberation of Majestic Lord Rwa Lotsāwa, the Yogin-Translator of Rwa, Mighty Lord in Magic Intervention.” There were extended translations of traditional pilgrimage guides for the Kathmandu Valley, including texts by the Fourth Khamtrul and the Sixth Zhamar hierarchs, for assignments where teams of students would race around the valley rim looking for an elusive footprint in stone or a guesthouse long in ruins that marked the turnoff of an old pilgrim’s trail. For many students these assignments were the first foray into field work methods, and Hubert’s careful guidance helped them approach collaborations with local experts ethically and with deep respect for diverse forms of knowledge.

One semester there was a project titled “The Mystery of the IV Brother Images, ’Phags pa mched bzhi” focused on the famous set of statues in Tibet and Nepal and based on new Tibetan materials that had only just come to light. Another examined the “The Tibetan World ‘Translated’ in Western Comics.” Finally, there was a classic of the genre that examined the creative nonconformity of the Bhutanese mad yogin Drugpa Kunleg in light of the American iconoclast composer and musician Frank Zappa: “A Dose of Drugpa Kunleg for the post–1984 Era: Prolegomena to a Review Article of the Real Frank Zappa Book.”

Frank Zappa was, indeed, another of Hubert’s inspirations and his aforementioned review included the following passage: “If there’s one thing I do admire in FZ, it is precisely these ‘highest standards’ and utmost professional thoroughness that does not allow for any sloppiness (in the name of artistic freedom or spontaneous freedom)…. At the same time, each concert is really different, [and]…appears as a completely spontaneous event.” Hubert’s life as a scholar, teacher, and mentor was a consummate illustration of this highest ideal.

Hubert is survived by his wife Nazneen Zafar; his daughter Cascia Decleer, son-in-law Diarmuid Conaty, and grandsons Keanu and Kiran Conaty; his sister Annie Decleer and brother-in-law Patrick van Calenbergh; his brother Misjel Decleer and sister-in-law Martine Thomaere; his stepmother Agnès Decleer, and half-brother Luc Decleer.

A traditional cremation ceremony at the Bijeśvarī Vajrayoginī temple near Swayambhū took place on Monday, August 30 at 8:30 AM.

༢༠༢༢ ལོར་རྒྱལ་སྤྱི་བོད་རིག་པའི་ཞིབ་འཇུག་ཚོགས་པའི་བགྲོ་གླེང་འཚོགས་ཐེངས་བཅུ་དྲུག་པའི་ཆེད་དཔྱད་རྩོམ་སྙིང་བསྡུས་གོང་འབུལ་གྱི་འབོད་བརྡ།

༄༅། །མཁྱེན་ལྡན་རིག་པའི་གྲོགས་མཆེད་ལགས།

ང་ཚོས་འདི་ནས་ད་ལམ་ཐུགས་སྣང་ཅན་གྱི་ཞིབ་འཇུག་པ་ཚོར་ཅེག་སྤྱི་མཐུན་རྒྱལ་ཁབ་ཀྱི་རྒྱལ་ས་པ་རག་ཏུ་ཕྱི་ལོ་ ༢༠༢༢ ལོའི་ཟླ་བ་ ༧ པའི་ཚེས་ ༣ ནས་ ༡༠ བར་འཚོགས་གཏན་ཁེལ་བའི་རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་བོད་རིག་པའི་ཞིབ་འཇུག་ཚོགས་པའི་བགྲོ་གླེང་འཚོགས་ཐེངས་བཅུ་དྲུག་པའི་ཆེད་རང་གི་དཔྱད་རྩོམ་སྙིང་བསྡུས་དེ་གོང་འབུལ་ཞུ་བར་བརྡ་འབོད་གཏོང་བཞིན་ཡོད། འཚོགས་ཐེངས་འདི་ཉིད་ཆར་ལེ་སི་གཙུག་ལག་སློབ་གྲྭ་ཆེན་མོའི་རིག་གནས་སློབ་གཉེར་སྡེ་ཚན་དང་ཅེག་ཚན་རིག་སློབ་གཉེར་ཁང་གི་ཤར་ཕྱོགས་རིག་པའི་སྡེ་ཚན་ཟུང་གིས་གོ་སྒྲིག་ཞུ་བཞིན་ཡོད།

འཚོགས་འདུའི་དེབ་སྐྱེལ་གྱི་ལས་རིམ་དེ་སྒོ་བཙུགས་ཡོད་པས། ད་ནས་བགྲོ་གླེང་ཚན་ཆུང་གི་འཆར་ཟིན་དང་སྒེར་གྱི་དཔྱད་རྩོམ་སྙིང་བསྡུས་རྣམས་གོང་འབུལ་ཞུ་ཆོག་པ་དང་། གོང་འབུལ་ཞུ་ཆོག་པའི་དུས་བཀག་བཅད་མཚམས་ནི་ཕྱི་ལོ་ ༢༠༢༡ ལོའི་ཟླ་བ་ ༩ པའི་ཚེས་ ༡༥ བར་དུ་ཡིན།

དེབ་སྐྱེལ་དེ་(Conftool)ཞེས་པའི་དྲ་རྒྱའི་མ་ལག་གིས་གོ་སྒྲིག་གནང་ཡོད་ཅིང་། མ་ལག་དེ་ཉིད་དབྱིན་ཡིག་དང་བོད་ཡིག་གཉིས་ཀའི་ཐོག་ཏུ་ཡོད། དཔྱད་རྩོམ་སྙིང་བསྡུས་དང་བགྲོ་གླེང་ཚན་ཆུང་གི་འཆར་ཟིན་གོང་འབུལ་ཞུ་བ་ལ།

༡༽ འདི་ནས་(Conftool)གྱི་ནང་དུ་ཐོ་ཁོངས་ས་དམིགས་ཤིག་བཟོས་གནང་རོགས།

༢༽ དཔྱད་རྩོམ་སྙིང་བསྡུས་དང་ཡང་ན་བགྲོ་གླེང་ཚན་ཆུང་གི་འཆར་ཟིན་གོང་འབུལ་གནང་རོགས།(ལམ་སྟོན་དགོས་མཁོ་བྱུང་ཚེ་ ༢༠༢༢ ལོའི་པ་རག་གི་རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་བོད་རིག་པའི་ཞིབ་འཇུག་ཚོགས་པའི་བགྲོ་གླེང་གི་དྲ་བྱང་ཐོག་དབྱིན་བོད་གཉིས་ཐོག་ནས་ཡོད།)

དབྱིན་ཡིག་དང་བོད་ཡིག་གང་རུང་བཀོལ་ནས་གོང་འབུལ་གྱི་འགེང་ཤོག་དེ་བཀང་གནང་རོགས།

ཁྱེད་ཀྱི་འཆར་ཟིན་དང་དཔྱད་རྩོམ་སྙིང་བསྡུས་དེ་ངོས་ལེན་བྱུང་བའི་སྐོར་གྱི་བརྡ་ལན་ནི་ཕྱི་ལོ་ ༢༠༢༢ ལོའི་ཟླ་བ་ ༡ པོའི་ཚེས་༣༡ འགྱངས་མེད་འབྱོར་ངེས་རེད། དེ་མཚམས་ཚོགས་འདུར་མཉམ་ཞུགས་ཆེད་མཐའ་མའི་དེབ་སྐྱེལ་མཇུག་སྐྱོང་ཡོང་བ་དང་། ཚོགས་དོད་གླ་རིན་འབུལ་ཕྱོགས་ལམ་སྟོན་ཡོང་གི་རེད།

སྔོན་རྩིས་བརྒྱབ་པའི་བགྲོ་གླེང་གི་ཚོགས་དོད་དམ་དེབ་སྐྱེལ་གྱི་གླ་རིན་ནི་ཅེག་སྒོར་༥༨༠༠(ཡུ་སྒོར་༢༣༠)ཡིན། དེའི་ཁོངས་སུ་ཚོགས་འདུ་ཧྲིལ་པོའི་རིང་གི་ཉིན་གུང་བཞེས་ལག་གི་དོད་ཀྱང་ཚུད་ཡོད། དེབ་སྐྱེལ་གྱི་གླ་རིན་དེའི་ཐོག །དོ་བདག་སོ་སོའི་འགྲིམ་འགྲུལ་དང་། བཞུགས་གནས་གོ་སྒྲིག དེ་བཞིན་མགྲོན་ཁང་གི་གླ་རིན་རྣམས་ཚོགས་ཞུགས་པ་རང་ངོས་ནས་ཐུགས་འགན་བཞེས་དགོས་པ་ཡིན། ང་ཚོས་བགྲོ་གླེང་འཚོགས་ཡུལ་གྱི་ཉེ་འཁྲིས་སུ་ཡོད་པའི་བཞུགས་གནས་མགྲོན་ཁང་ཁག་གི་ཐོ་གཞུང་ཞིག་ལོགས་སུ་མཁོ་སྤྲོད་གསལ་བསྒྲགས་ཞུ་ངེས་ཡིན། ཐོ་གཞུང་དེ་ཉིད་པ་རག་གི་རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་བོད་རིག་པའི་ཞིབ་འཇུག་ཚོགས་པའི་བགྲོ་གླེང་གི་དྲ་བྱང་ཐོག་ཏུའང་འཇོག་གི་རེད།

དཔལ་འབྱོར་གྱི་འཁོས་བབ་ཞན་པའི་ཞིབ་འཇུག་པ་དང་བོད་ནས་ཕེབས་པའི་ཞིབ་འཇུག་པ་རྣམས་གདམ་གཞིར་བཟུང་ནས་ཚོགས་དོད་མཐུན་འབྱོར་གྱི་གྲངས་ཚད་ཉུང་ངུ་ཞིག་ཀྱང་གྲ་སྒྲིག་ཡོད། ཡུལ་སྐོར་དང་གཞན་ཡང་རིག་གཞུང་འཁྲབ་སྟོན་ཡང་གོ་སྒྲིག་བྱ་ངེས་ཡིན་ཡང་དེའི་གླ་རིན་འཕར་མ་འབུལ་དགོས། རིག་གཞུང་འཁྲབ་སྟོན་གྱི་སྐོར་དེ་རྗེས་སུ་གསལ་བསྒྲགས་ཞུ་ངེས་ཡིན།

བགྲོ་གླེང་འཚོགས་ཡུལ་གཙོ་བོ་ནི་ཆར་ལེ་སི་གཙུག་ལག་སློབ་གྲྭ་ཆེན་མོའི་རིག་གནས་སློབ་གཉེར་སྡེ་ཚན་གྱི་གཞུང་ལས་ཐོག་ཁང་གཙོ་བོ་(ཡ་ནཿཔ་ལ་ཁྷཿཐང་། ༢ པ་རག ༡)དེ་ཡིན།

ད་ལྟའི་ནད་ཡམས་ཀྱི་གནས་སྟངས་ལ་གཞིགས་ན་འཚོགས་ཡུལ་དང་འགྲིམ་འགྲུལ་ལ་འབྲེལ་བ་ཡོད་པའི་འགྱུར་བ་དང་དཀའ་ངལ་ཁག་གཅིག་འཕྲད་སྲིད་པར་ཤེས་ཚོར་ཡོང་གི་འདུག་པས། ང་ཚོས་གནས་སྟངས་ལ་ལ་བབས་ལྟ་བྱས་ཏེ་འགྲིམ་འགྲུལ་ལ་ཉེ་བར་མཁོ་བ་གནས་ཚུལ་འཕར་མའི་ཐོ་གཞུང་སྐབས་མཚམས་སོ་སོར་པ་རག་གི་རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་བོད་རིག་པའི་ཞིབ་འཇུག་ཚོགས་པའི་བགྲོ་གླེང་གི་དྲ་བྱང་ཐོག་ཏུ་ཁ་གསབ་བྱ་བར་འབད་རྩོལ་ཞུ་ངེས་ཡིན། དེ་ལྟར་ནའང་གནས་ཚུལ་འདིའི་སྐོར་རང་རང་དང་འབྲེལ་བའི་དབང་འཛིན་མི་སྣའི་བརྒྱུད་ནས་ངེས་བརྟན་བཟོ་དགོས་པའི་འགན་འཁྲི་དེ་ཚོགས་ཞུགས་པ་རང་ཉིད་ལ་ཡོད།

བཀའ་འདྲི་ཞུ་དགོས་པ་གང་ཞིག་མཆིས་ཚེ་ ༢༠༢༢ ལོར་པ་རག་གི་རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་བོད་རིག་པའི་ཞིབ་འཇུག་ཚོགས་པའི་བགྲོ་གླེང་གི་གློག་འཕྲིན་ཁ་བྱང་བརྒྱུད་ནས་ང་ཚོར་འབྲེལ་བ་གནང་རོགས།

པ་རག་ཏུ་མཇལ་ཡོང་།

16th IATS Seminar 2022 – Call for Submissions

Dear Colleagues,

We are now inviting interested scholars to submit their proposals for the 16th IATS Seminar, which will be held in Prague, Czech Republic, Prague (3–9 July 2022) and hosted by the Faculty of Arts, Charles University and the Oriental Institute of the Czech Academy of Sciences.

The registration program is now open. You can submit a panel proposal or an individual paper. The deadline for submission is September 15, 2021.

The registration is hosted by Conftool and is available in English and Tibetan. To submit a proposal, please:

- create an account in Conftool here;

- submit your proposal (if necessary, instructions in English and Tibetan are available on the Prague IATS 2022 website).

Please use English or Tibetan to fill out the submission form.

You will receive information about the acceptance of your proposal by January 31, 2022.

You will then be asked to complete the final registration of participation and transfer the conference fee payment.

The anticipated registration fee for the Seminar is 5800 CZK (ca. 230 EUR). The registration fee includes lunches throughout the conference. IATS attendees will be responsible for their own transportation, arrangement of accommodation, and accommodation costs, in addition to the registration fee. We will provide a list of available lodging options close to the venue in a separate announcement. The list will also be available on the Prague IATS website.

A small number of fellowships will be available, with preference given to scholars from Tibetan areas and to financially disadvantaged scholars. Sightseeing and further cultural programs will also be available but at additional cost. The cultural offers will be announced later.

The principal venue for the Seminar will be the main building of the Faculty of Arts of Charles University (nám. Jana Palacha 2, Prague 1).

With regard to the current pandemic situation, we are aware that there may be certain difficulties and changes connected to travel and the venue. We will follow the situation and try to maintain an updated list of additional travel requirements on the Prague IATS 2022 website. However, the attendees are responsible to confirm this information with the respective authorities.

For any inquiries please contact us via the Prague IATS 2022 e-mail.

See you in Prague!

Helga Uebach (1940-2021)

Helga Uebach, who is well known in Tibetan Studies for having dedicated most of her academic career to the Wörterbuch der tibetischen Schriftsprache and for her contributions to Old Tibetan studies, passed away on 8 February 2021. The quiet voice of my esteemed colleague and predecessor in the dictionary project fell silent at the age of 80 years.

Helga Uebach was born on 19 July 1940, in Munich, went to school in a place nearby called Attenkirchen and took her final exams of the gymnasium (secondary school) in 1959. One year later, she started studying Indology and Tibetology under Helmut Hoffmann and Mongolian Studies under Herbert Franke who both influenced her scientific career.

Helga Uebach was born on 19 July 1940, in Munich, went to school in a place nearby called Attenkirchen and took her final exams of the gymnasium (secondary school) in 1959. One year later, she started studying Indology and Tibetology under Helmut Hoffmann and Mongolian Studies under Herbert Franke who both influenced her scientific career.

As a student of Helmut Hoffmann, Professor for Indology and Iranian Studies at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, she was the first scientific employee who joined the dictionary project already in 1964. Three years before her dissertation she started to work in the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities, in the Kommission für zentralasiatische Studien that Hoffmann founded together with Erich Haenisch, Professor of East Asian Culture and Language Studies in 1954. After she retired in 2005 from her full-time profession, she still assisted the dictionary project with specific questions, particularly those related to Old Tibetan.

Having been research assistant in 1963 at the Seminar for Indology and Iranian Studies (now the Institute for Indology and Tibetology), she joined the dictionary project in 1964, when the collection of terms has just begun. At the same time, she worked on her dissertation in Indology, completing it in 1967. The subject was an edition and translation of the Nepālamāhātmya, an appendix of the Skandapurāṇa. This text describes the holy places of the Kathmandu valley, including the associated cults from a Śaivite perspective. The work was published in 1970 in a series of the Philosophical Faculty of Munich University (Das Nepālamāhātmyaṃ des Skandapurāṇaṃ. Legenden um die hinduistischen Heiligtümer Nepāls, München: Fink Verlag, 1970.) In the same year she obtained a full position as research assistant at the Bavarian Academy.

Some years previously, in 1960, with the support of the Rockefeller Foundation Helmut Hoffmann had invited two Tibetan scholars to Munich to join the dictionary project. One of the two was Jampa Losang Panglung, who also studied Tibetology and Indology at the LMU. After completing his Magister degree in 1976, he joined Helga Uebach at the Wörterbuch der tibetischen Schriftsprache, where they both worked until their retirement. The early years of the dictionary project were laborious, and the project was affected by the tremendous changes caused by the arrival of Tibetan exiles in India. Beginning in the 1970s, Tibetans started publishing large quantities of Tibetan texts. In these pre-computer times, Helga Uebach and Jampa L. Panglung spent their time filling card index file-boxes with handwritten notes on Tibetan terms for the dictionary project.

Apart from these lexicographical studies, Helga Uebach worked predominantly on Tibetan cultural history, with a special focus on the 7th to 9th centuries, the period of the early Tibetan kingdom. Her scholarly interests also included the history of Ladakh and document studies. From the early 1980s these interests, that also provided material for the dictionary, led her and her colleague on several field trips to India and Tibet. In those years, Tibetan Studies were at an early stage, and Tibetan publications were still rare. To collect further material for dictionary project, Helga Uebach photographed inscriptions in Ladakh and Tibet, as well as documents held in the Library of Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamsala. However, the increasing volume of Tibetan publications in India that was now possible thanks to technological progress partly overran these efforts to add all this additional material.

One of her major works at this time was a translation of the chronicle by Nelpa Pandita (Helga Uebach: Nel-pa Paṇḍitas Chronik Me-tog phreṅ-ba. Handschrift der Library of Tibetan Works and Archives; tibetischer Text in Faksimile, Transkription und Übersetzung, München: Kommission für Zentralasiatische Studien, Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1987 (Studia Tibetica. Quellen und Studien zur tibetischen Lexikographie, 1). She had discovered this historical source, that had long been considered to be lost, in the Library of the Tibetan Works and Archives in Dharamsala while she was photographing all the Tibetan documents in 1982. With this publication, Helga Uebach established the series “Studia Tibetica. Quellen und Studien zur tibetischen Lexikographie” at the Bavarian Academy of Sciences and Humanities. Moreover, she translated Rolf A. Stein’s work Tibetan Civilization into German (Die Kultur Tibets, Edition Weber Berlin 1993).

In November 1973, one year before her full employment in the Academy, Helga Uebach and Jampa L. Panglung organised the invitation of the Dalai Lama for his very first visit to Europe. Supported by senator Günter Klinge and Gertraut Klinge, who were both also sponsors of the dictionary project, it was possible to invite the Dalai Lama to Munich, where he met scholars of the Bavarian Academy, politicians as well as Tibetan and Mongolian Buddhists.

Just over ten years later, in the summer of 1985, she and Jampa L. Panglung were co-convenors of the fourth seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies in Schloss Hohenkammer, close to Munich. More than 100 participants from 22 countries took part in this event. The results were published in proceedings: Helga Uebach and Jampa L. Panglung (eds): Tibetan Studies. Proceedings of the 4th Seminar of the International Association for Tibetan Studies, Schloss Hohenkammer ‒ Munich 1985, München: Kommission für Zentralasiatische Studien, Bayerische Akademie der Wissenschaften, 1988 (Studia Tibetica. Quellen und Studien zur tibetischen Lexikographie, 2). She was also the Secretary General of the IATS, a position that she retained for the Munich seminar, as well as for the fifth, that was held in Narita in 1989.

By the time Helga Uebach retired in 2005 she has been working on the Wörterbuch der tibetischen Schriftsprache for forty-one years. In the same year, she published the first fascicle of the dictionary. Until her unexpected death on 8 February 2021, she was still an active figure in Tibetan Studies, and continued regularly to publish articles of exemplary scholarship, mainly in the field of Old Tibetan.

Petra Maurer

Josef Kolmaš (1933-2021)

Josef Kolmaš, who was one amongst the rather small group of founders of modern Tibetan Studies, passed away on February 9th, 2021, at the age of 87 years. He is known by the international academic public for the work he published in English, which focuses on historiographical topics and China-Tibet relations. But this is only a part of his legacy. Among the Czech public he is better known as a prolific translator of numerous books concerning Tibet, China and India from various languages: Tibetan, Chinese, Latin, Russian, English and German.

I remember Josef Kolmaš as a very supportive mentor. Meticulous and strict, but also a kind man endowed with a very distinctive sense of humour. The circumstances of his life were indeed fascinating, and rich in unusual paradoxes.

Josef Kolmaš with his teacher Narkyid Ngawang Thondup and Hugh E. Richardson at the first IATS seminar in Oxford, 1979 (source: Kolmaš, Josef, Tibet: dějiny a duchovní kultura. Praha: Argo, 2004).

He was born in south Moravia (the southeastern part of the Czech Republic), which is known as an island of Catholic faith in the sea of otherwise lukewarm religious sentiments of Czech society. Born in Těmice as the eldest of five children in the family of a bricklayer in 1933, he enrolled at the Jesuit church gymnasium (secondary school) in Velehrad just at the end of the Second World War in 1945. Following the communist coup d’état in 1948 the persecution of the church and its institutions was in the air.

The communist regime targeted the Velehrad church gymnasium and seminary in the spring of 1950 as part of the so-called Action K. Seventeen-year-old Kolmaš was interned with other students of the gymnasium and novices of the seminary in Bohosudov, North Bohemia, for almost six months.

‘Teachers and the young novices were taken away. Teachers were imprisoned, but the Communist Party and the government did not know how to deal with the novices. Eventually, the novices were kept interned until September,’ he recalled as he recounted his time in the so-called ‘centralised monastery,’ which was effectively a camp guarded by the communist police. Every day he had to line up in the yard as a prisoner, and to listen to the propaganda reading of the political commissioner. He and others were forced to liquidate the local library by throwing volumes out of the windows. The communist regime did not allow anyone to visit him, and he was allowed to go outside only accompanied by guards. He was not even allowed to inform his parents that he was alive until three months later.

Later, he was forced to work on the construction of the Klíčava dam near Kladno, where he levelled the slopes and built roads around the reservoir. ‘They brought some female members of the Communist Youth union who were eager to socialise and dance with us. They were apparently attempting to re-educate us,’ he recollected in the interview for the Memory of Nations project. He eventually ended up in the abolished Franciscan monastery in Hájek near Prague, and only then was he released.

He then continued his studies at the gymnasium in Kyjov. His teacher Ladislav Dlouhy supported his interest in Oriental languages. He showed Kolmaš New Orient (Nový Orient), a journal in which a manual of Chinese was being published in instalments.

Josef Kolmaš with the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, 1978 (photo: Doboom Tulku, source: Kolmaš, Josef, Tibet: dějiny a duchovní kultura. Praha: Argo, 2004).

Following his graduation in 1952 he was accepted for studies of Czech and Russian languages at the University of Olomouc. In the environment of the planned economy of the communist regime a formal authorisation was required for studies. The number of the students in each subject at the universities was planned and strictly prescribed. The authorisations were then distributed to the classes of graduates from the secondary schools. The gymnasium of Kyjov received just two authorisations for the graduates, one of them for the study of Czech and Russian languages at the University of Olomouc.

But Josef Kolmaš was determined to study the Chinese language, which at that time was taught only at Charles University, in Prague. Following his graduation, he decided to visit the Minister of Education in person and to persuade him to provide him with official permission. The minister of Education at that time was Eduard Štoll, a representative of the Stalinist wing of the Communist Party. Amazingly, the minister agreed to meet the young graduate. During their discussion he phoned Jaroslav Průšek, an influential Czech sinologist and lecturer in Chinese at the University. And following Kolmaš’s visit to Průšek, his way to the study of Chinese was opened.

Kolmaš studied Chinese in the years 1952-1957. There were ten students of Chinese in the class, which was quite a large number at that time. Since 1949 the People’s Republic of China had been a partner of the communist regime. Josef Kolmaš recollected the words of the minister of information Václav Kopecký after his visit of China at that time: ‘Thanks to the victory of communism in China the Earth’s axis has tilted in the direction of progress.’ Kolmaš was taught Tibetan as a second language by Pavel Poucha, a specialist in Mongolian Studies and the Tocharian language. What the study of Tibetan was like at that time was described to me some years ago by Kolmaš: “Poucha taught me the Tibetan letters and explained the way they work during the first class. For the next class he brought a Tibetan translation of the New Testament. He gave it to me saying: ‘You have the Czech version of it, so you can make the effort yourself!’”

Josef Kolmaš with the Dalai Lama and Czech indologist Dušan Zbavitel. Prague, 1990 (photo: J. Ptáček, source: Tändzin Gjamccho, Svoboda v Exilu: autobiografie 14. Dalajlamy. Praha: Práh, 1992).

Following his graduation, Kolmaš was offered a postgraduate stipend at the Central Institute for Nationalities in Beijing in 1957. He spent two years there between 1957 and 1959. His stay there proved to be crucial for his future research within the field of Tibetan Studies. He was the first foreign student to study there. At the same time, this was also Kolmaš’s first trip abroad. It was the time of the Great Leap Forward campaign (1958–1960) and also the start of the Great Chinese Famine (1958–1962) that left a toll of 35–45 million deaths. Kolmaš recollected some scenes that illustrated the situation in China at that time. He remembered the head of the Institute catching flies and collecting them in a small paper bag in the toilet as part of the Four Pests Campaign aimed at eliminating rats, flies, mosquitoes and sparrows. Kolmaš also recollected his enormous shame when the head of the Institute asked him for a piece of sugar for his children, who had never seen it. Kolmaš was given provisions at the Soviet Embassy, which significantly alleviated the concerns of his daily life in Beijing.

He spent some time with another foreign Tibetologist at the Central Institute for Nationalities: Yuri Parfionovich (1921–1990), who was a member of the Moscow Oriental Institute of the Academy of Sciences. Parfionovich had fought as a soldier in the Red Army before his studies, had taken part in the Soviet-Finnish War, and was a member of an espionage group. As a soldier he had participated in the capture of Berlin, and had celebrated the end of the Second World War in Prague. Kolmaš remembered him as a good companion who was nevertheless a heavy drinker. He was haunted by nightmares from his soldier’s past, especially the moments when he was forced to shoot his own close friends dead.

Kolmaš always remembered his own teachers in Beijing with a feeling of gratitude. One of them was Narkyid Ngawang Thondup (1931–2017). Kolmaš recollected that he had no information about him after leaving Beijing. But later in 1969, during an audience with the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, in India, he mentioned his name in the conversation. The Dalai Lama gestured to his secretary and after a while Narkyid Ngawang Thondup appeared in front of a greatly surprised – and moved – Kolmaš.

But his principal teacher of Tibetan was the Chinese scholar Yu Daoquan (1901-1999), who also had studied in Paris from 1934 and had taught at SOAS, in London, from 1938. He is known as a founding figure of Tibetan Studies in China and the compiler of the Chinese-Tibetan Dictionary of Colloquial Lhasa Tibetan (Bod rgya shan sbyar gyi lha sa’i kha skad tshig mdzod, 1983). Kolmaš frequently spoke about his unselfishness and recalled him as a ‘real bodhisattva.’ Yu Daoquan had good contacts with Tibetans in Derge. Thanks to this connection Kolmaš has been able to order a full Derge print of the Kanjur to be sent to the Prague Oriental Institute. Also, Kolmaš’s later works on Derge Prints and the Genealogy of the Kings of Derge were made possible through his teacher Yu Daoquan.

During his studies in Beijing, Kolmaš also made a hand-written copy of the 14th century Tibetan chronicle The Mirror Illuminating the Royal Genealogies (Rgyal rabs gsal ba’i me long). Translating it into Czech and publishing it under the title Zrcadlo králů (Mirror of Kings) much later in 1998 was the fulfilment of one of the dreams he had conceived during his studies in Beijing.

A few years ago I met with András Róna-Tas, the Hungarian linguist and the first president of IATS, in Szeged. He recollected that in those days he had been working on the Monguor language. Knowing that Kolmaš was in Beijing at the Central Institute for Nationalities, he kept writing letters addressed to Kolmaš, asking him to transcribe the real pronunciation of various Monguor words. He had never had a chance to listen to the Monguor language he was researching at that time, and it was only through Kolmaš that he could learn the actual pronunciation of it.

While staying in Beijing, Josef Kolmaš conceived a plan to visit Derge. He was able to set off there only in 1959. On arriving in Lanzhou he could see streams of railway trucks with tanks and cannons heading for Tibet. The uprising in Lhasa has started following the escape of the Dalai Lama to India. While in Lanzhou, he received an urgent telegram ordering him to return to Beijing immediately.

After his return from Beijing in 1959 he worked at the Oriental Institute of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. It was a period of hard work transforming the initial inputs from his stay in China into the results that would be recognized within the international community of Tibetologists. The regime in Czechoslovakia relaxed in the 1960s, and he was able to work as a visiting lecturer at the Australian National University in Canberra in 1966. Following the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968, the political situation was again the determining factor in academic research. Despite that and the fact that during that period of time, until the Velvet Revolution in 1989, he was obliged to translate political documents from Chinese, he also managed to continue his academic work. In 1969 and 1978 he visited India, where he worked with Lokesh Chandra. In 1979, in Oxford, he was among the founding members of the International Association for Tibetan Studies.

Following the Velvet Revolution in 1989, the Oriental Institute underwent changes. He served as a director between the years 1994–2002, and retired in 2003.

He was married to Marie, with whom they had a son, Vladimír, and a daughter, Ivana. Sadly, in 2006 his wife Marie passed away, and he himself spent the last five years of his life in a nursing home following a serious illness.

In his English-language works he took advantage of his knowledge of both Tibetan and Chinese. His most valuable publications include works on China-Tibet relations. These include Tibet and Imperial China (Canberra 1967), The Ambans and Assistant Ambans of Tibet: A Chronological Study (Prague 1994), Four Letters of Po Chü-i to the Tibetan Authorities (808-810 A. D.) (ArOr 34, 1966), and Ch’ing shih kao on Modern History of Tibet (1903-1912) (ArOr 32, 1964). These contained new information and pioneered the use of Chinese sources for Tibetan historiography. Another focus of his research was Derge and the printing house there. Among the publications dedicated to this topic are A Genealogy of the Kings of Derge (Prague 1968), the Prague Collection of Tibetan Prints from Derge I-II (Wiesbaden – Prague, 1971), and The Iconography of the Derge Kanjur and Tanjur (New Delhi 1978).

The numerous books he translated into Czech from various languages are not known to the international public. Among others, he translated the well-known story of Nangsa Öbum (Nang sa ’od ’bum gyi rnam thar) from Tibetan, the Mirror of the Genealogy of Kings (Rgyal rabs gsal ba’i me long, mentioned above) and Songs of Milarepa (Mi la ras pa’i mgur ’bum). From Chinese he translated the travelogues of the Chinese monks Xuanzang and Faxian, describing their journey to India; his translations from Latin include letters written from China by 18th-century Czech missionary Karel Slavíček, while from Russian he translated the travelogue to Lhasa by Gombojab Tsybikov. Through such translations of essential texts, he is well-known to the Czech public interested in Asia.

There used to be a saying ascribed to St. Benedict on the door of Kolmaš’s office: Serva ordinem et ordo servabit te, ‘Preserve order and order will preserve you.’ His personal passage through the turbulent times of history, and the legacy of his work, are a reflection of the seriousness with which he applied this advice in his personal life.

Daniel Berounský

Prague, 25 February 2021

David Seyfort Ruegg (1931-2021)

David Seyfort Ruegg was born in 1931 and passed away 2 February 2021. After an initial training at SOAS and the University of Zürich (1948-1950), his university education was primarily in Paris, where he studied Indology under Jean Filliozat and Louis Renou and Tibetology under Marcelle Lalou and Rolf Stein. David Seyfort Ruegg’s work has ranged over most aspects of Indian and Tibetan Studies. However, two interests come back repeatedly: the philosophy of the buddha-nature (tathāgatagarbha) and the philosophy of the middle way (madhyamaka). David Seyfort Ruegg has held professorial positions in several major universities – Leiden, Seattle, Hamburg. He also was a visiting professor and lecturer at the University of Toronto (1972), State University of New York (1974), the School of Oriental and African Studies of the University of London (1987), as well as an invited professor at Collège de France, in Paris (1992), at the University of Vienna (1994), Kyōto University (1995), SOAS (1998) and Harvard University (2002). He was a Sanskritist and a Tibetologist and at one time or another has held chairs in Indian Philosophy, Buddhist Studies, and Tibetan.

16th IATS Seminar 2022 – First Announcement

རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་བོད་རིག་པའི་ཞིབ་འཇུག་ཚོགས་པའི་བགྲོ་གླེང་འཚོགས་ཐེངས་བཅུ་དྲུག་པ།

འཚོགས་ཡུལ། པ་རག ཅེག་སྤྱི་མཐུན་རྒྱལ་ཁབ།

འཚོགས་ཡུན། ཕྱི་ལོ་(༢༠༢༢)ཟླ་བ་(༧)པའི་ཚེས་(༣)ནས་(༩)བར།

16th IATS Seminar

Prague, Czech Republic, July 3–9, 2022

གསལ་བསྒྲགས་ཐོག་མ།

First Announcement

རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་བོད་རིག་པའི་ཞིབ་འཇུག་ཚོགས་པའི་བགྲོ་གླེང་འཚོགས་ཐེངས་བཅོ་ལྔ་པ་དེ་བརྗིད་ཉམས་དང་། སྤུས་གཙང་གི་ཕྱུར་བ། རྒུན་ཆང་སྤུས་ལེགས་བཅས་ཡིད་དབང་འཕྲོག་པའི་ཁོར་ཡུག་ཏུ་མགྲོན་འབོད་གྲུབ་རྗེས་ད་ལམ་རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་བོད་རིག་པའི་ཞིབ་འཇུག་ཚོགས་པའི་བགྲོ་གླེང་འཚོགས་ཐེངས་བཅུ་དྲུག་པ་དེ་ཁོད་ཡངས་དང་། གསོལ་ཀྲུམ། བྷི་རག་བཅས་ཀྱི་ཀློང་ནས་འདུ་འཛོམས་བྱ་རྒྱུ་ཡིན་པར་ཡིད་སྤོབས་ཆེན་པོས་སྙན་སྒྲོན་ཞུ་བཞིན་ཡོད། རྒྱལ་སྤྱིའི་བོད་རིག་པའི་འབྲི་གཡག་རྣམས་གླིང་ཆེན་ཡུ་རོབ་ཀྱི་ལྟེ་དཀྱིལ་ཏེ། ཅེག་སྤྱི་མཐུན་རྒྱལ་ཁབ་ཕྱོགས་སུ་བང་རྩལ་རྒྱུག་འགྲན་གནང་ནས། ཕྱི་ལོ་(༢༠༢༢)ལོའི་ཟླ་བ་(༧)པའི་ཚེས་(༣)ནས་(༡༠)བར་རྒྱལ་ས་པ་རག་གི་ཆར་ལེ་སི་གཙུག་ལག་སློབ་གྲྭ་ཆེན་མོར་དངོས་ཕེབས་ཀྱིས་ང་ཚོར་གཟིགས་མཐོང་བསྩལ་ངེས་རེད།

Following the 15th Seminar, hosted in a charming environment of grace, delicate cheese, and fine wine, we are proud to announce that the 16th IATS Seminar will be marked by earthiness, meat, and beer. The IATS yak will gallop to the heart of Europe, the Czech Republic, and will honour us with its presence in Prague on July 3–9, 2022 at the Faculty of Arts, Charles University.

ད་ལམ་གྱི་འཚོགས་ཐེངས་འདི་ཉིད་ཆར་ལེ་སི་གཙུག་ལག་སློབ་གྲྭ་ཆེན་མོའི་རིག་གནས་སློབ་གཉེར་སྡེ་ཚན་དང་ཅེག་ཚན་རིག་སློབ་གཉེར་ཁང་གི་ཤར་ཕྱོགས་རིག་པའི་སྡེ་ཚན་གཉིས་ཟུང་སྦྲེལ་གྱིས་གོ་སྒྲིག་ཞུ་རྒྱུ་དང་། གོ་སྒྲིག་འགན་འཛིན་པ་ནི་(རིག་གནས་སློབ་གཉེར་སྡེ་ཚན་གྱི་)ཌ་ཎི་ཡལཿབྷེ་རོན་སི་ཀི་ལགས་དང་(ཤར་ཕྱོགས་རིག་པའི་སྡེ་ཚན་གྱི་)ཡར་མི་ལཿཔི་ཏ་ཅི་ཀོ་ཝ་ལགས་རྣམ་པ་གཉིས་ཡིན།

The Seminar will be organized jointly by the Faculty of Arts, Charles University and the Oriental Institute, Czech Academy of Sciences. The convenors are Daniel Berounský (Faculty of Arts) and Jarmila Ptáčková (Oriental Institute).

དཔྱད་རྩོམ་སྙིང་བསྡུས་དང་བགྲོ་གླེང་ཚན་ཆུང་གཉིས་ཀྱི་འབོད་བརྡའི་སྐོར་དེ་ཕྱི་ལོ་(༢༠༢༡)ལོའི་འགོ་སྟོད་དུ་གསལ་བསྒྲགས་སྙན་སྒྲོན་ཞུ་རྒྱུ་ཡིན་ཞིང་། དེའི་ནང་བགྲོ་གླེང་གི་ལས་འཆར་སྙན་ཞུ་འབུལ་སྟངས་དང་། བགྲོ་གླེང་འཚོགས་འདུར་དེབ་སྐྱེལ། བཞུགས་གནས་མགྲོན་ཁང་གི་གདམ་ག བགྲོ་གླེང་གི་འཚོགས་དངུལ་བཅས་དང་འབྲེལ་བའི་གནས་ཚུལ་རྣམས་རྒྱས་པར་འབུལ་གྱི་ཡིན། འཚོགས་ཞུགས་པ་རྣམས་ཀྱིས་རང་གི་འགྲིམ་འགྲུལ་དང་བཞུགས་གནས་མགྲོན་ཁང་གི་གླ་རིན་རྣམས་རང་ངོས་ནས་འགན་འཁུར་བཞེས་རྒྱུར་ཐུགས་འཇགས་འཚལ།

The call for abstracts and panels will be announced early in 2021, including detailed information regarding the submission of proposals, registration, accommodation options, and the conference fee. IATS attendees will be responsible for their own transportation and housing costs.

པ་རག་ལ་ཕེབས་པར་དགའ་བསུ་ཞུའོ།། །།

Welcome to Prague!

Vítejte v Praze!